Knitting the Climate Crisis: Verena Winiwarter Uses Handicraft to Make Complex Science Tangible

By Patricia McAllister-Käfer

As she arrives on this summer morning in a café in Vienna’s Wieden district, Verena Winiwarter is not in a good mood. The environmental historian is just back from visiting the ski resort Galtür in Tyrol, along with journalists. There, the 59-year-old says, you can see the Jamtalferner – one of the few remaining glaciers in the eastern Alps – melting before your eyes. Disappearing glaciers, species going extinct, catastrophic forest fires – researchers like Winiwarter are recording these huge losses, which affect all of humanity, in their local environments. “I am one of those people who feel emotionally caught up,” Winiwarter says.

Verena Winiwarter is one of the most acclaimed scholars in the country and a pioneer of interdisciplinarity, of teaching and researching across academic disciplines. Born in Vienna, she has degrees in history and chemistry, a researcher of both culture and nature – two broad fields that most academics regard as discrete. As an environmental historian, she has been working for decades on the relationship between society and environment: the causes and effects of the climate crisis are increasingly dominant topics. Winiwarter has published articles, written books, spoken on podiums about the importance of protecting the environment – and has had to stand by and watch as politicians hesitate and the glaciers melt. This has left traces.

Recounting her trip to Tyrolean Paznaun, she is analytical and composed. But nevertheless, she says she still feels “environmental grief”, which is common amongst those studying sustainability. The phenomenon describes the psychological impact of environmental destruction, which climate scientists of Winiwarter’s generation have seen gradually advancing over the course of their careers. Some of them are suffering from anxiety, grief, or burnout as a consequence.

But Winiwarter has found her own vent for her environmental grief – a distraction that is perhaps not just good for her own mental health, but also for the climate. Even if at first glance it seems like she must be joking. Winiwarter is enlisting handicraft – as an academic approach to the climate crisis.

Just recently she published a study in the Opinion Series of the renowned Austrian Academy of Sciences, together with two German colleagues, the philosopher and mathematician Ellen Harlizius-Klück and the textile conservator Charlotte Holzer. The title: “Weaving the SDGs: A reflection on quadrangles and embodied practices.” Put simply, Winiwarter argues in the study that the United Nations’ sustainability development goals (SDGs) would be easier for people to understand if they were… woven. Is handicraft a new tool in academic practice? This would be a rather unconventional hypothesis for a scholar of her status.

Verena Winiwarter

But Winiwarter believes her assertion, and right here in the café she starts to pull out of her rucksack the tools of her research: wool, knitting needles and home-made punched cards. She says she discovered handicraft as a method of thinking through her hands, of understanding interrelations, and simultaneously also of “schaffen,” creating something. In the sense of Angela Merkel, she adds. The German chancellors famous 2015 slogan “Wir schaffen das” (we’ll manage; we’ll do it) on the refugee movements is for Winiwarter an expression of assurance and reassurance – in the midst of crises, even in the climate crisis, there is still time to act.

For many years, Winiwarter has been knitting socks as a statement against the climate crisis. She calls her designs “fire and ashes“ or “ecological resilience“ and auctions them for ICEHO on Twitter to raise funds for early career scholars. As we talk, Winiwarter begins to knit – she is currently engaged in a pair of socks with green and brown stripes, for a friend.

The sustainable development goals woven into Winiwarter’s knitwear bemused her academic colleagues. Winiwarter is sympathetic. “Don’t forget, I’m not working in an arts department” she says. Winiwarter teaches at the Institute for Social Ecology at the University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences. She started her career in the early 1980s with a degree in chemical engineering, for a while she worked in a laboratory at Vienna University of Technology. In 1991, she started studying history and communication, and she went on to launch the field of environmental history in Austria. In 2007, Winiwarter became the first professor of environmental history at the University of Klagenfurt.

Winiwarter tries to explain complex processes simply. In her narrative book Geschichte unserer Umwelt, which she wrote together with geo-ecologist Hans Rudolf Bork, she takes the reader on 66 time-travel journeys through global environmental history, from the Danube to Easter Island. In 2015, the book won the Austrian prize for Science Book of the Year.

When Winiwarter looks out of the Café in the direction of the Wien River, she doesn’t just see the urban street scene, but also the view as it was two hundred years earlier. “The Wien River was a stinking brown stew back then” she says, “but people used to bathe in it in the summer anyway.” Winiwarter recounts how the abattoir at Margartengürtel used to empty its waste into the Vienna river in the nineteenth century, while the carters used it to water their horses and the tanners to rinse their hides. The river foamed and stank. “Tanneries are still a massive environmental problem today,” she says. But nowadays that problem is in India or Bangladesh. Globalisation, Winiwarter tells me, also means that the negative impact of production is felt elsewhere, while we skim off the products, many of which are made under terrible conditions and without any consideration of the environmental effects.

The United Nations set out its sustainable development goals in 2015 in part to address this imbalance. The 17 goals – including world peace, food security, ecological protection – are the first attempt to set out a global agenda for development. They are not legally binding however, and whether and how they can be realised by 2030 is a question for each state to decide. Progress thus far has been underwhelming, and the SDGs have scarcely made a ripple in the public imagination.

Winiwarter is convinced that one problem is the official communication of the agenda. She has studied the SDGs intensively, in 2019 she organised an international conference on this topic at the Austrian Academy of Sciences. She disputes that the 17 goals each stand alone, in their own square, each bearing a number and their own colour-code. A “catastrophic separation,” according to Winiwarter, “the agenda should be a web!” Moreover, the SDGs have been promoted with cheap items made of plastic and metal, for keyrings and the like. “And I just think, how can they produce SDG trash?” Winiwarter says, “but they do…”

Winiwarter takes two slender multicoloured cotton bands out of her rucksack and smooths them out on the table. This is her version, a different, woven interpretation of the SDGs. Over the course of her summer holiday in 2019 she immersed herself in tablet weaving, a three-dimensional weaving technique that can be produced using simple materials and without a loom. At least in theory. “The first time I tried to do it, I realised that I hadn’t grasped a single thing.” Grasping something new is both a mental and a physical process, Winiwarter is convinced of that. She tries to feed thread through one of the punched cards from her rucksack – and fails. She smiles and says, “you see, it’s the resistance of the material that fascinates me.”

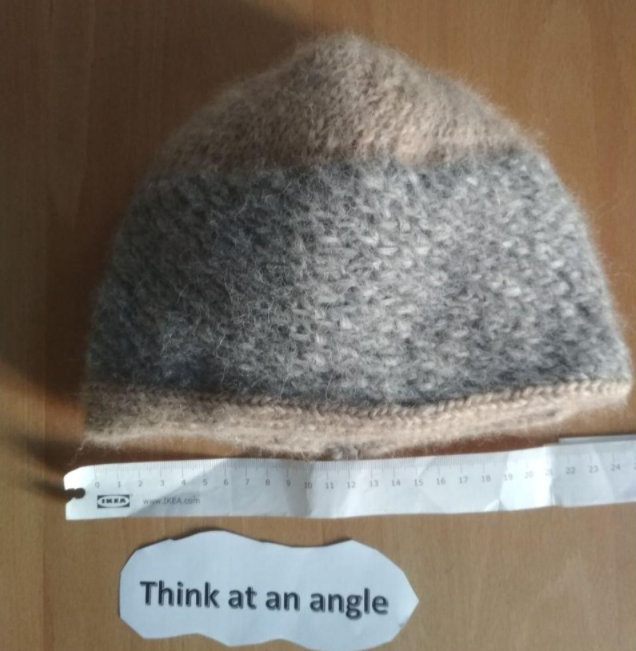

Verena Winiwarter in one of her knitted hats, later sold at one of ICEHO’s auctions.

Knitting, on the other hand, is a means for Winiwarter to deal with ecological grief. She noticed, she tells me, how restorative it feels to produce something that is “not part of the capitalist mode of efficiency.” Winiwarter only has five pairs of her own knitted socks in the drawer. They don’t need to be washed so often, she reports, and when they get holes, she darns them. “If we have less stuff, then we have more time. And it reduces our footprint.”

Is Winiwarter’s handicraft in fact activism – or has it become escapism, a way of avoiding reality? In fact it’s the opposite, the professor tells me, it allows her to keep working. Once, women were charged with knitting as a form of “bourgeois domestication.” But “I feel like I cannot be domesticated, because I knit.” Winiwarter says, knitting has taught her to accept her own limitations. It’s not the end of the world if she drops stitches in her pattern. “That’s a sign that our society should become more error-friendly,” she says, and now I can hear reassurance in her voice. It’s as if the past two hours of knitting have given her a whole new lease of energy.

Translation by Katie Ritson. The original (German) version of this article was published on 22 July 2021 in Die Zeit Österreich.